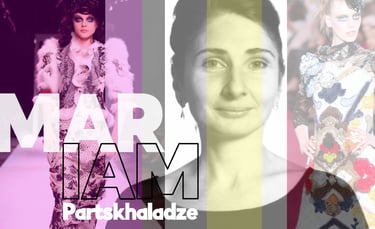

The Transformative Touch of Mariam Partskhaladze

From Caucasus peaks to Parisian runways, ancient felt finds its contemporary voice. Mariam Partskhaladze has spun magic for Christian Lacroix, Jimmy Choo, and a constellation of other high-end brands.

Elizabeth Lotz

In an age of digital production, felt offers something that synthetic materials are designed to erase. It contains texture and tactility that can only emerge through human effort.

Designers who work with Mariam gain access to properties no machine can replicate. At the same time, the ecological cost of synthetic materials becomes increasingly difficult to ignore. Chemical processing, energy waste, and rapid obsolescence reveal just how destructive efficiency can be.

Felt-making demands little energy. It relies on renewable resources. It produces goods meant to endure across decades, not seasons. This is a form of refusal. It upholds practices that industrial systems would rather eliminate. What we often call progress, with its drive for speed, low cost, and disposability, may actually be a system built to erode meaning. It wears down craft, culture, memory, and skill.

DecaDialogue: Ten Questions, One Artisan

In this recurring series, we explore the spaces where tradition survives mechanization.

Q. Your practice is rooted in the ancient art of Georgian felt-making, yet your designs feel deeply contemporary. How does working with such a historic technique influence your sense of creative possibility today?

A. Since early childhood, I have been passionate about fashion, fabrics, and I question their various manufacturing techniques and their history. In 2003, I discovered the ancestral method of felt-making. This technique became my preferred means of expression. Felt, while being a raw, primitive support, is also a material that offers richness and freedom of creation. It lends itself well to artistic expression and opens possibilities for contemporary creation. For this reason, I always seek to enrich my work by transposing other creative techniques onto this material.

I work a lot with transparent or openwork supports, combining different textures, embedding other animal or plant fibers into the wool, pieces of fabric, cut parts, sewn or molded in the mass. This marriage of an ancestral technique with modern materials allows me to access original aesthetic innovations. I try thus to show how, from the coarsest material—simple sheep’s wool—and primary colors, one can create infinitely feminine and delicate objects. Sometimes I feel like I am weaving, painting, and sculpting all at once.

Q. Do you find that your most original ideas emerge through intuitive, tactile exploration, or do they begin with a clear mental image that you consciously shape into form?

A. I am more tactile. A small piece of fabric catches my eye: colors, a pattern, the design of a lace scrap, all these textile treasures, which tell a story, are my sources of inspiration. Of course, there is nature, a book, a film, a meeting, or an event.

Q. Your pieces often appear to emerge organically, yet they serve precise aesthetic and functional roles. How do you navigate the balance between improvisation and control in your creative process?

A. Before starting a piece, I often make small samples to see how the materials react to felting. I calculate the shrinkage. And while making the piece, I observe regularly, adjust, and measure step by step until drying.

Q. Many artists describe constraints as either a cage or a catalyst. How do boundaries, such as working within a tradition or for a specific client, shape the way you innovate with fabric and form?

A. Participating in collections or live performances is a constant enrichment. Guided by the spirit of each collection or performance, but also carried by a tremendous wind of freedom, I find myself in a perpetual search for creativity with each new collaboration. Working with other designers, couturiers, stylists, or costume-makers pushes me toward other artistic discoveries. Seeing the result, at fashion shows, exhibitions, or performances, represents a magnificent reward for me.

Q. You’ve collaborated with major fashion houses like Christian Lacroix and Christophe Josse. How does the creative dialogue in collaboration differ from when you create independently?

A. When I create for them, I feel like I step into their skin and see through their eyes. I like being guided by a few reference points, the spirit of the collection, and colors, while still having the freedom to create. I also really enjoy the exchanges between us! For my own projects, I follow my intuition and my ideas.

Q. Working with your hands, especially with a medium as ancient and sensory as felt, must create a deep emotional connection. Do you consider your emotional state part of the “material” you work with?

A. Both. It depends on the situation. Events that touch me, joy, sadness, and anger, are transformed into creation.

Q. Cultural identity seems central to your work, not just in technique, but in spirit. How has your Georgian heritage evolved within you as a creative force, especially while living and working in France?

A. I navigate between two worlds and take the best from both.

Q. Do you see the act of making as a kind of meditative or psychological practice? What inner states tend to accompany your most fulfilling periods of creativity?

A. Both. It depends on the situation. Events that touch me—joy, sadness, anger—are transformed into creation.

Q. Is there a creative decision or turning point in your journey that didn’t feel rational at the time but proved essential in shaping your voice as an artist?

A. Between 2008 and 2010, I did a training in haute couture embroidery, which fascinated me a lot, and since then, I have navigated between these two techniques.

Q. If you could leave behind one idea, not an object, but a truth, about the nature of creativity, what would you want future generations of makers to understand?

A. Creation is life. To be oneself.

From the mountain villages of Georgia to the ateliers of Paris, Mariam Partskhaladze reveals that the system we are told is unshakable may, in fact, be hollow. Advancement might sometimes look like regression. Efficiency might disguise waste. Innovation might destroy the very knowledge it claims to improve. Resistance is not something that waits for permission. It is already present in the hands that continue to create.

Fashion theorist Elizabeth Wissinger describes our closets as a "laboratory of disposability," a symptom of a fashion industry that has built a consumption engine selling "self-expression" through style, values, identity, and aspiration; basically a choreography of illusion. In truth, we are just fueling a system that consumes cultural heritage and generates quarterly profit while logging every purchase we make. That’s efficient, sure, and cold.

This machine operates on what economists call planned obsolescence: the quicker garments fall apart or lose relevance, the more often we are compelled to buy new ones. It’s just so lucrative. Why make something that will last when the system is designed to turn tradition into trash? This is a consumption engine designed to manipulate cultural norms based on artificial scarcity, manufactured desire, and serviceability.

The strategies are not far from the practices of Edward Bernays, who used psychological principles to direct public behavior regarding consumption, which we know, industries subsequently took and applied to emotional branding and signaling status. In this case, however, we are not consumers. By every definition of the term, we are "users."

The Anomaly in the Machine

In 2003, Georgian textile designer Mariam Partskhaladze entered the Caucasus Mountains and found a living knowledge system refined through centuries of practice and quiet refinement. The people she met still knew how to create things that endure. She hadn’t gone there searching for an alternative to industry; she went to observe, to learn. And every day in those mountain villages, she saw something that raised a gentle and quiet challenge to the idea that mass production is progress.

For thousands of years, these communities had perfected the art of felt-making, and it wasn’t just a charming pursuit; it was necessary for survival. Their process relied on human judgment, including the ability to sense when to stop, adjust, or change course mid-process. We can rarely, if ever, recreate this sensitivity through machines and, to a much lesser degree, in standardized processes. Their understanding of fiber behavior had an intuitive precision to it.

In many respects, it foreshadowed what contemporary material science would eventually state. Industrial processes can replicate some outcomes, though at the expense of critical properties. Felt is particularly resistant to duplication. Machines will typically substitute softness to achieve strength, or breathability for durability. Traditional processes, however, succeeded in achieving a balance of those properties.

What Mariam witnessed was cultural knowledge encoded with technical logic. In contrast, industrial production appeared crude rather than advanced.

The Economics of Subversion

Based in her atelier in the Drôme mountains in France, Mariam has achieved what the fashion system insists is impossible: she has made traditional craft financially viable without allowing it to become subservient to mechanization. Her clients not only include Christian Lacroix, Jimmy Choo, and Christophe Josse, but also the Opéra de Paris. This is not a capitulation to the mainstream but rather a calculated, tactical way of engaging with the fashion system that refutes the industry's narratives about what is practical, efficient, and inevitable.

Her collaboration with Christian Lacroix brought hand-felting into haute couture, where the word innovation often signals the replacement of craftsmanship with software. In collaboration with Jimmy Choo, she had a part in designing accessories, accessing these human properties of strength and subtlety that mark her material sensibility, even outside the medium of textiles. These qualities do not come from programming; they arise from human touch. When the Opéra de Paris commissioned her work, it placed its trust in the idea that hands, not machines, still hold a certain authority.

The Knowledge They Cannot Automate

In Georgia's felt-making tradition, there is subtle manipulation of heat, pressure, and timing. These are not abstract variables. Too much heat will destroy the wool. Too little pressure and the fibers will never fuse. Mass production cannot account for this kind of nuance, and algorithms are not equipped to listen to the material.

Mariam often incorporates older materials into her work, including lace, silk, and embroidery. Each commission requires its own mix of durability, texture, and structure. She achieves these outcomes through variation; it is an active continuation of a living science based on skilled labor, and her projects suggest, discreetly, how limited industrial processes truly are.

The Conspiracy of Preservation

Since the 2006 Saint-Étienne Design Biennale, Mariam has collaborated with Georgian embroiderer Nâna Metreveli, demonstrating that cultural wisdom is sustained most powerfully through intergenerational dialogue and collective practice, rather than individual resistance. Metreveli’s embroidery carries religious and cultural symbols that commercial markets cannot easily absorb. Mariam's felt serves to ground the structure, and Metreveli's stitching provides narrative weight. What they create together is a testament that preservation is not passive but instead active, deliberate work on a daily basis that resists any temptation to streamline or optimize.